У США у 2019 році покажуть нові фільми та ретроспективу Абеля Феррари.

Eric Kohn, Indiewire

The filmmaker has a busy slate and a major retrospective at MOMA this year. Here, he reflects on the rocky path to a happier life.

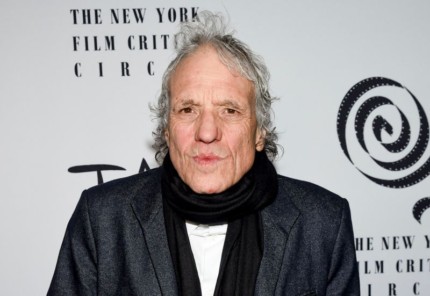

For the first three decades of his career, Abel Ferrara was a seminal New York filmmaker whose gritty tales of furious pariahs, addicts, and rebels made Martin Scorsese’s “Mean Streets” look like “Mr. Roger’s Neighborhood.” But Ferrara fled New York after 9/11 and found a new life abroad. On a recent evening in Rome, he stood on the porch of his home, thousands of miles from the city that put him on the map, and contemplated his history of battling for final cut.

“You can’t paint a mustache on a Mona Lisa just because you fucking buy it,” he said, wearing a pair of scruffy headphones as he stared into a Skype session on his laptop. His leathery features and wisps of long white hair gleamed against a shadowy backdrop. “You dig what I mean? I’m working in my own language.”

With Ferrara, meaning can be an elusive thing. The heated 67-year-old talks in sharp bursts of vulgarity, half-formed philosophies, and profound cultural inquiry, but if you roll with his rhythms they start to take on a poetry akin to his distinctive filmography. From the early B-movie offerings of “Driller Killer” and “Ms. 45” through the morally complex character studies of “Bad Lieutenant” and “The Funeral,” Ferrara excels at digging into the psychology of deeply troubled urbanites, and mining the pathos within.

After a drug-fueled meltdown, countless burned bridges, and a fresh start in Europe, Ferrara’s still at it. While many of his movies have been embroiled in controversy, deemed unreleasable in the U.S., or gone out of print, he has barreled ahead. His 2019 slate might be his most prolific year ever — four movies on the horizon, and a major new retrospective of the achievements that put him on the map in the first place.

At the Tribeca Film Festival, he’s premiering “The Projectionist,” an amiable documentary about Cyprus-born theater manager Nick Nicolau, whose New York journey stretches back to running adult film houses and exploitation showcases in the early ‘70s, when Ferrara’s career first took root. On May 10, his 2014 biopic “Pasolini,” which stars his best friend and regular collaborator Willem Dafoe as the late Italian filmmaker, will finally receive a U.S. release after buyers passed on its steep price tag years ago.

A week after “Pasolini” opens, Ferrara’s low-budget narrative feature “Tommaso,” a semi-autobiographical drama also starring Dafoe opposite the director’s real-life wife and infant daughter, will screen out of competition at the Cannes Film Festival. And Ferrara has already wrapped production on another long-gestating project with Dafoe, in a surreal journey inspired by Carl Jung, Jack London, and who knows what else.

In any case: Abel Ferrara is back, baby. “It’s funny how all the shit happens at once,” he said. “As long as somebody’s watching the films, I can live with it. It all seems like a lot, everything at once, but we’re always doing the same thing.”

Regardless of how he chooses to characterize it, there’s no question that Ferrara has reached a measure of stability after several rocky chapters. After his gruff Harvey Keitel vehicles “Dangerous Game” and “Bad Lieutenant,” he fought with top studio brass on his ambitious 1993 remake “Body Snatchers,” then drifted back to low-budget efforts like his Christopher Walken vampire thriller “The Addiction.” He blamed 9/11 on ruining New York for him, both financially and culturally, but the drugs didn’t help, either.

“When I first got sober, I had to stay away from New York,” he said. “I wasn’t going to risk it.” Even Italy wasn’t totally safe. “I’m not going to Napoli for a long time,” he said. “These are cities that are very interconnected with my drug use.”

Ferrara kept making New York movies while living abroad, but they often hit snags that kept them out of theaters: His Cannes-acclaimed “Go Go Tales,” a Frank Capra-meets-strippers crowdpleaser that should have been a comeback story, ran into rights issues that screwed its domestic release; a few years later, he got into a public spat with IFC Films over the R-rated cut of “Welcome to New York,” his bawdy take on the Dominique Strauss-Kahn saga. Ferrara still winced at the decision by his sales agent and longtime confidant, Wild Bunch’s Vincent Maraval, to side with IFC.

“Vince is a big supporter and a very good friend, but when we came to that film, it was like he was stepping into the place where they wanted me to make a change that I wasn’t going to make,” Ferrara said. “For 10 years, he never crossed that line. It was shocking. You can’t have final cut of my movie, because that’s the only gig I got.”

Ferrara faced similar challenges in the studio arena at a trepidatious moment for Hollywood productions: He signed on to “Body Snatchers” while Spike Lee made his own studio foray with “Malcolm X” and Oliver Stone directed “JFK.” All three directors fought with executives over their singular visions, but for Ferrara, it cemented the idea that he belonged in a different arena. “I would definitely not go through what I went through to make that film,” he said. “It was a miracle that I survived that thing.” He shrugged. “What does Biggie say? ‘Bigger the money, bigger the problems.’” He almost got it. “All money comes with strings attached, you know?”

These days, Ferrara lives within his means. He gestured at the living room adjacent to his porch, where a guitar was propped up on an unkempt couch. “This is what you get for like a normal rent in fucking Italy, as opposed to living in a 12 by 12,” he said. He doesn’t miss New York. “I just don’t want to kill myself morning, noon and night, live in a box, eating poison food,” he said. “Everybody I see in New York is just working around the fucking clock just to fucking pay the rent. I mean, the quality of life in that town is fucked, man. Maybe it always was.”

Or maybe he outgrew it? “Yeah.”

With “Tomasso,” Ferrara has crafted what may end up being the closest he comes to a cinematic confession. He has produced several scrappy documentaries like “The Projectionist” over the years, appearing on-camera to interrogate his subjects while interjecting with his own experiences, but “Tommaso” is poised to explain how he wound up with his wife, Christina, with whom he shares a four-year-old.

Or maybe not. “We’re creating this kind of new character who’s an interesting guy,” said Ferrara, who shot the movie at home. “It’s not really me and it’s not really … not me. It’s more specific to me, but once Willem starts playing, it’s a dangerous game.” Dafoe lives next door to Ferrara and they often trade ideas. There is an element of oneupmanship to the way they compare New York bonafides. “I was in Union Square, so Willem and the Wooster Group seemed like they were in fucking Miami,” Ferrara said, referencing the experimental theater collective where Dafoe got his start. “I lived around where Andy Warhol was, and that was like the artistic center.”

When Ferrara circles back on his glory days, his tough-guy exterior gives way to a wistful air. Considering the MOMA retrospective, he said, “It seems like one long home movie to me. But it’s funny. I’m just thinking how the new stuff is going to click.” He made peace with the inaccessibility of his work long ago, at one point joking that anyone interested in his work could just download illegal torrents.

“If a guy likes to sit home in his own house, he has OCD, he don’t like people, he loves movies, what do you do?” Ferrara said. “Pick him up and sit him with 500 people and give him some stale popcorn and say, ‘Here, this is a great experience?’ I’ve been in some of these theaters! I’ve been in crack houses that had better projection!”

Ferrara cackled. Making “The Projectionist” led him to remember his formative years at New York arthouses, where provocative movies like Ken Russell’s “The Devils” and Fellini’s “Satyricon” inspired him. “You’ve got to get out of your house, too,” he said. “I wanted to go to the fucking movies just to be with a girlfriend.” These days, “I can’t even go to the movies, because I’m a 42nd Street kind of spectator,” he said. “I’m screaming and yelling and talking. I get thrown out of most theaters.”

Ferrara’s spiky demeanor and turbulent storytelling has always made some viewers uneasy, but current standards for political correctness haven’t exactly changed him. “When you’re a filmmaker, you’ve got to be totally free and you’ve got to express yourself,” he said. “You’ve got to be into your unconscious. You’ve got to start by respecting yourself, and then you’ve got to respect everybody else. But there can’t be any restrictions.”

Ferrara’s work has a unique identity in today’s cultural landscape — at once problematic and socially conscious to a degree that puts much of his output ahead of the curve. Though his 1981 rape-revenge thriller “Ms. 45” was a seminal work of feminist ire, “Bad Lieutenant” included a disturbing scene in which the main character masturbated in front of two helpless women that it’s hard to imagine passing muster today. “This attitude of political correctness — I mean, I lived through women’s liberation in 1973,” he said, as if referencing time spent in the armed services. “One day, our girlfriends all just moved out on us because of Betty Friedan’s book [‘The Feminine Mystique’]. I went through the women’s revolution, and the idea of oppression, and, yeah, I get it.”

He wasn’t quite sure what to make of #MeToo, Time’s Up, or really any other effort to instigate systematic change. “Every other revolution of my generation, in the late ’60s and ’70s, it just kind of disappeared,” he said. “Now, maybe it’s back. Power corrupts us, so you’ve got to be careful. You’ve got to be on guard.” He looked restless as he considered his rate of production in the last few years. “You don’t have to be on your knees waiting for anyone to accept your movie,” he said. “Just show the fucking thing!”

“Abel Ferrara Unrated” runs May 1 – 31 at MOMA. “The Projectionist” premieres at the Tribeca Film Festival on April 28, 2019.

Eric Kohn, Indiewire, 27 квітня 2019 року