Bethany Allen-Ebrahimian, Foreign Policy про «Тотем вовка» Жан-Жака Анно, який Китай не зміг висунути на «Оскар».

Wolf Totem is a spectacular film, but its soul is missing. That’s just how Beijing wants it.

On Oct. 8, when the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences released its list of submissions for the Best Foreign Language Film Academy Award, Wolf Totem wasn’t on it. The Academy’s disqualification of the Chinese-French co-production, long rumored to be the ruling Communist Party’s choice for this year’s submission, was technical — with a foreign director and three of four screenwriters also non-Chinese, the film had too much foreign creative influence to qualify as Chinese. This dashed the country’s latest, greatest hope for a Chinese Oscar winner. (Its replacement, the romantic comedy Go Away Mr. Tumor, seems a poor substitute). But even if the film had stayed in the running, an Academy award would likely still have proved elusive — for in order to be released in the world’s largest authoritarian country, Wolf Totem had to compromise the heart of its message.

Adapted from the semi-autobiographical novel published in 2004 by Chinese author Jiang Rong, Wolf Totem follows a Chinese student, Chen Zhen, who is sent from the capital city Beijing to the steppes of Inner Mongolia in 1967 during the Cultural Revolution, a time of great upheaval when Communist ruler Mao Zedong sent millions of educated youth into the countryside. Chen is assigned to a group of Mongol nomads who teach him how to herd flocks and fend off wolves, natural predators with whom the Mongols live in an uneasy symbiosis. Nearby agricultural settlements had begun to encroach on the wild steppe, edging out both the Mongols and the wolves. When local officials order the nomads to exterminate the wolves and kill all their offspring as a perceived threat to human habitation, Chen, who admires the wild animals, secretly captures and raises a cub. Despite Chen’s love for the wolves, and for the traditional Mongol way of life, in the end he is unable to save either.

The book upon which Wolf Totem is based — widely praised both inside and outside China, and translated into English by famed translator Howard Goldblatt — is in some respects a daring political manifesto, castigating broader Chinese society as well as specific government economic and social policies of the Cultural Revolution that decimated not just the natural environment but also Mongolian society, such as forced agricultural collectivization. The film adaptation initially seemed destined for glory as well, until its unexpected drop from Oscar consideration in early October. But the film itself is also flawed. Despite French director Jean-Jacques Annaud’s insistence that he felt no official pressure to paint Chinese history in overly rosy tones, the film adaptation gutted the book’s political critique and pinned the ecological fallout to a generic, inevitable advance of human civilization, rather than identifiable party policies.

The film’s message at face value seems to be that the power of human civilization, if abused, can destroy both natural habitats and the people and animals that rely on them. It’s an important and timely message, to be sure. China’s breakneck economic growth over the past few years has been accompanied by an equally dramatic devastation of its natural environment. According to recent studies, about one-fifth of farmland there is contaminated, almost two-thirds of its underground water is unfit for human use, and air pollution contributes to up to 1.6 million deaths each year. It’s also a small step forward for China’s tightly circumscribed media environment. Despite the environmental crisis and a new wave of government initiatives to address it, major media productions highlighting the crisis — and by implication, the government policies and lack of environment oversight that have driven it — remain limited. A major environmental exposé, Under the Dome, went viral as soon as it was released online in late February, racking up over 100 million views in a matter of days — only to be wiped from the Chinese Internet soon after. Wolf Totem, by contrast, has enjoyed implicit state backing, rumored to have been selected by the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film, and Television (SAPPRFT), China’s secretive media regulator, as this year’s choice for Oscar Best Foreign Film submission until the Academy disqualified it.

The major problem with Wolf Totem, however — and perhaps the source of the vaguely empty plot and superficial character development that earned it middling marks on Chinese movie-rating platform Douban — is not what it depicts but what it doesn’t. The Cultural Revolution, with its accompanying violence and the heavy-handed state emphasis on ethnic unity, and accompanying suppression of minority identity, culture, and way of life, is the elephant in Wolf Totem’s living room. From 1966 to 1976, the Cultural Revolution turned Chinese society upside down, as party leader Mao Zedong called upon young party zealots to rid the country of counterrevolutionary elements and “feudal” customs. Hundreds of thousands perished. Wolf Totem’s opening scene captures the early enthusiasm of the Cultural Revolution: Beijing’s iconic Tiananmen Square teems with crowds of people and buses as students load up to head out to the countryside. But filmmakers allotted exactly two words as explanation for the ideologically based upheaval that shut down the university system for a decade, crippled the economy, decimated social trust, and battered ethnic traditions. It was, as Chen narrates, a “chaotic period.”

Most egregious is the movie’s whitewashing of what really happened to the Mongol ethnic minority during that time. The official party line has long been that China’s 56 ethnic groups get along harmoniously and that the Chinese government has brought nothing but prosperity and opportunity to the country’s border regions. But the relationship between the Mongols of the nominally autonomous Chinese region of Inner Mongolia and the politically and demographically dominant Han Chinese there is a complex one that can, in some respects, be considered a case of “internal colonialism.” This term, sometimes invoked by scholars outside of China but rejected by official Chinese narratives, points to government promotion of Han settlement in traditionally minority regions, as well as what often amounts to political and cultural domination. During the Cultural Revolution, the government intensified state-sponsored migration of Han Chinese farmers to Inner Mongolia. This policy was far from apolitical, according to Morris Rossabi, a professor at the City University of New York who specializes in Inner Asian history. The Chinese state “wanted control over an area that might be troublesome and had been troublesome in the past,” Rossabi told Foreign Policy in a phone interview. The influx of Han farmers, combined with intrusive social and economic policies which forced Mongols out of herding and into newly built factories, sparked a “series of violent encounters” between Mongols and the Han-dominated Chinese state, said Rossabi. Mongols “felt they were being repressed by the regime and [felt] swamped by the Han colonists coming in.” According to Rossabi, approximately 25,000 Mongols died in the ensuing violence. The farms also resulted in desertification, since the arid Mongolian steppe can be ill-suited for agriculture.

But Wolf Totem obscures this history. The result resembles what 1991 Academy Award winner Dances With Wolves might have been like if it were illegal in the United States to openly discuss the atrocities that the U.S. government systematically committed against Native Americans, or to portray meaningful disharmony between white settlers and indigenous peoples. The Mongol nomads ride their horses to greet and cheer the Han students arriving by bus, and adopt two young Chinese men into their village without a hint of friction. The settlers who desecrate a sacred lake and crowd out the nomads are largely presented as Mongols themselves, who have opted to give up the nomadic lifestyle to “keep up with the times,” as one character put it. The aging village head, in a role uncomfortably similar to the “noble savage” trope, speaks inexplicably flawless Mandarin Chinese, and Chen also picks up Mongolian with seeming ease, meaning that language barriers make no appearance in this cinematic depiction of China’s borderlands where to this day language barriers persist. The primary evil figure is, admittedly, a Han Chinese local official, but the harsh policies he enforces wreak mostly ecological damage, affecting the Mongol village only indirectly. Forced collectivization, violent uprisings, and the resulting deaths of thousands of Mongols are left out entirely.

The hand behind the censorship is far from invisible. La Peikang, the head of SAPPRFT, serves as the gatekeeper to the Chinese film market, and he’s not afraid to showcase his influence. His name, listed as “Presenter,” appears early in the opening credits, second only to Jean Jacques Annaud, the director.

To be sure, even with its ethnocentrism and political censorship, Wolf Totem is far cry from the redface of Hollywood’s early depictions of Native Americans as savages. Key Mongol characters are played by actual Mongols, who frequently speak Mongolian on screen. Nomadic society is characterized in an almost rosy light, rather than as ignorant, violent, or uncivilized. “There is a certain amount of sympathy for the Mongolian nomads,” Rossabi emphasized, referring to the book (he has not seen the movie), which did “not [portray] them as a conservative people living in a backwards era.” And at times, the movie seems to draw as close to the official line as possible without crossing it. In one scene, the elderly village chief tells Chen that “the problem with us Mongols is that most of our history wasn’t written by us, but by our enemies.” Given the context, and that most of what the modern world knows about Mongol history comes through either Chinese or Persian sources, it’s clear — though not directly stated — who these enemies were. The chief then tells Chen, a cinematic self-conscious reference to Jiang’s later recording of his experience in novel form, “You know Mandarin. Maybe one day you can write down our stories.”

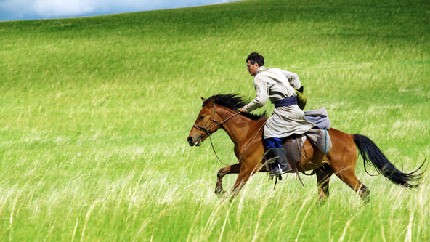

The rest of the film achieves mixed results. The wolves, trained for the film from the time they were cubs, act out human expressions of collective revenge. One scene, of Mongol warriors on horseback chasing the wolf pack which is attempting to drive a herd of prize horses onto a frozen lake, was shot with minimal assistance from computer imaging, a stunning cinematic feat which perhaps makes the whole two hours of movie worth it. The cinematography is sweeping and beautiful, though with perhaps one too many slow-motion takes of the wind rippling through their fur as the wolf pack wisely observes human actions from nearby clifftops. The result is indeed regal, but the film somehow lacks the spirituality and intimacy of the haunting American 1983 film classic Never Cry Wolf. That may be because it’s hard to intuit the depth of the man-wolf relationship when, for much of the film, Chen keeps the wolf cub chained by the neck in a small pen, interacting with the animal largely at feeding time only.

Even with its imperfections, Wolf Totem was an indisputable sensation in China, rising to the box office number two spot shortly after its February release in China and grossing $110 million there. Months after its release, it was still the talk of the town. On a flight a few months ago from China’s capital city of Beijing to the far western regional capital of Urumqi, I struck up a conversation with the friendly young Chinese man sitting next to me. “Have you seen Wolf Totem?” He asked me. When I said I hadn’t, he launched into a rapturous 15-minute account. He was so eager for me to see the movie, at that time not yet released in the United States, that he asked for my email address and promised to send me an (assumedly pirated) digital file. Two weeks later, after our respective trips had concluded, he did.

Wolf Totem was clearly widely watched — an eye-popping 120,000 web users rated the movie on Douban, and more than 55,000 left comments — but Chinese viewers still expressed largely similar criticisms regarding superficial character development, unsatisfying plot, and misrepresentation of Mongol history and society. The movie performed moderately on Douban, with an overall rating of 7 out of 10, a reasonably good rating, but performing better than just 48 percent of adventure films rated on the site according to site metrics. “The wolves were better actors than the people,” went the most up-voted comment, and the “core” of the film, the wolf as a totem for man, was “dug a little shallow.” Another Douban user wrote in a popular comment, “The movie made the Mongols from the east” — in the film, the Mongol settlers who had adopted the modes of an agricultural society — “into the despicable characters.” One comment criticized the director for avoiding the topic of Mongolian nationalism, which prevented the movie from “explaining the significance of the wolf as totem for the Mongolian people.” As a result, the post’s author concluded, “the audience had to endure two dull, uninteresting hours of man and nature.”

But many still praised the film. As one Douban user who ranked the film eight out of 10 wrote, “Though it does have its shortcomings, it’s rather rare for this kind of movie to be released in China.” Part of the problem may simply be one that Hollywood frequently botches as well: the inherent difficulty of turning a best-selling novel into an equally compelling movie. Paul Pickowicz, professor of history and Chinese studies at the University of California, San Diego, and author of several books on Chinese cinema, told FP in an email that “the novel is so powerfully otherworldly and so deeply psychological that turning it into an equally innovative film is virtually impossible.”

Despite its problems, for better or worse the movie still rings true for some. “What’s so amazing,” wrote one Chinese web user, “is that even though this story happened 50 years ago, it still tells the story of society today.”

Bethany Allen-Ebrahimian, Foreign Policy, 14 жовтня 2015 року