Жан-Жак Анно про відмову Американської кіноакадемії взяти до розгляду його «Тотем вовка», висунутий Китаєм у номінації «Найкращий іншомовний фільм».

Rhonda Richford, The Hollywood Reporter

“American movies are made by global talent but they are still American movies. Why is it that foreign-language movies are treated differently?”

Few filmmakers have experienced such remarkable reversals of fortune while straddling the divide between Hollywood and China — the world’s largest and second-largest film markets, respectively — as French director Jean-Jacques Annaud.

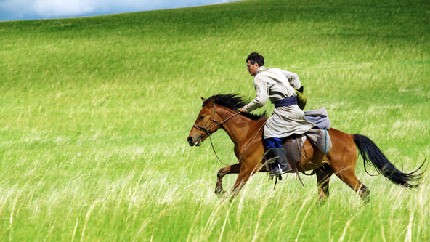

After the release of his Brad Pitt-starring drama Seven Years in Tibet in 1997, Annaud was reportedly informed that he would be denied entry to China for the rest of his life because of official outrage over his portrayal of the politically sensitive topic of Tibet. Remarkably, Annaud was able to repair his relationship with the Chinese, returning to the country to shoot the period epic Wolf Totem, a China-France co-production backed by China Film Group, the country’s central state studio, that was released in China earlier this year.

But Annaud now finds himself blocked from the opposite direction. After Wolf Totem grossed over $110 million in China, the film was selected by China as the country’s official submission for the best foreign-language film Oscar. However, in a letter dated Oct. 5, the Academy declared the film ineligible after determining that the production, starring Chinese actors speaking Mandarin and Mongolian but directed by a French director, is simply not Chinese enough. While the Chinese-French co-production boasted an 80-20 financing split, the Academy’s beef is with the team of top creatives – it cited not only director Annaud, but also director of photography Jean-Marie Dreujou, editor Reynald Bertrand, and American composer James Horner – amongst those in “creative control” of the film, which it determined violated its rule that a production must be “largely in the hands” of the nominating country’s citizens or residents.

As recently as Sept. 21, sources close to China’s Film Bureau confirmed to The Hollywood Reporter that Wolf Totem would be the country’s submission, so it came as an international shock when 31-year-old Chinese director Han Yan’s lightweight comedy Go Away Mr. Tumor appeared on the Academy’s official list of foreign-language category contenders released on Oct. 8.

An Academy spokesperson confirmed to THR that it was decided during a meeting on Oct. 2 that Wolf Totem didn’t meet the criteria as a Chinese submission. The move marks a turnabout from 2014, when Philippe Muyl’s The Nightingale, a film similarly top-heavy with Frenchmen, was deemed eligible as China’s official entry in the category. Annaud, who won a foreign-language Oscar in 1977 for his Ivory Coast submission Black and White in Color, spoke with THR about the controversy, calling the Academy’s decision “confusing and arbitrary.”

How did you hear that the Academy had decided Wolf Totem was ineligible?

I got a call the night of October fifth to tell me that they [the China Film Group] had received a notification from the committee and Mark Johnson. He is the chair of the Motion Picture Academy foreign language film selection committee — long title. And their verdict came from the fact that, in my view, they misread who is the producer. The producer is Chinese and there are two French co-producers, but the entity in charge of the production is the China Film Group. It’s the biggest Chinese film company and the chairman is Mr. La Peikang. And according to the bilateral treaty between China and France, this is a Chinese-French co-production with 80 percent Chinese backing. It was shot entirely in China, in the Chinese language, with an entirely Chinese cast, a Chinese crew of 600 and only seven people from France. They are: the two co-producers – myself and Xavier Castano – the director of photography, the editor, the continuity supervisor, the final sound mixer [and the lead screenwriter]. I think another very negative element for the selection committee was that the music was composed by [American] James Horner, although it was recorded partially in Beijing.

What was the shock for all of us is that the rules of the selection committee are not clear and widely available, and I just read that the committee wants to have the guarantee that the artistic control is in the hands of nationals from the submitting country. Therefore, I’m asking the following: why is it that actors are not part of the balance or the quota, and why is it that the producer, who is the initiating producer and in charge of 80 percent of the budget, is not considered on the list of people in control? So now do films have to have a director from the submitting country in order to compete? Or who exactly is in “creative control”? Because in co-productions, we have treaties [that establish point value for creative positions to determine which country receives majority credit], so a number of points from China and a number of points from France and the two administrations check if it’s valid and that’s a very simple rule.

The film submitted last year by China was also directed by a Frenchman, [Philppe Muyl’s The Nightingale]. I just called him and he said it went through [the selection committee], and so last year it was okay for the Academy to accept a movie from China co-produced by France with a French director, French crew, and French co-producer [Steve Rene]. Why is this year different?

The project was Chinese in origin, correct?

Yes, a 100 percent Chinese production. The production company was called Forbidden City and the president of this company had bought the rights to the novel and came to see me in Paris. He really had the initiative and convinced me. I was very happy to be convinced, I must say, but it was his initiative. But then he was offered the vice presidency of China Film Group and he took the movie with him, and it’s only then that we suggested making it a co-production to fit the reality of the project, because some of the artistic partners would come from France. But it was still an 80 percent Chinese movie that we shot entirely over there. And what’s bizarre is that it’s a profoundly Chinese story shot entirely in the country and depicting a very specific moment in China, something that is seen by the Chinese as conveying Chinese history and culture.

You sent a letter to the Academy explaining this?

Right.

When?

I sent this letter the next day, the sixth [of October]. And since then we have exchanged daily emails but I know they won’t change their decision. I am just curious about one thing: why is it that American cinema has been thriving since the origin and making it in the global market and taking the directors they feel appropriate, the musicians, the DOP, costume designers? American movies are made by global talent but they are still American movies. Why is it that foreign-language movies are treated differently?

Do you think the Academy is discriminating against you a bit because you’ve already won an Oscar for foreign-language film from a different country in the past?

I don’t feel it’s personal, no. I feel maybe it is more against China than against myself. I didn’t take it personally at all.

Why do you feel it’s a decision against China?

I think, probably unconsciously, with China being such a big market, they probably look at China a different way than they would look at Togo or Sao Tome, so they have acted instinctively but I don’t know. I’m just answering the question. But I think China is a rival and therefore the rival is not treated in the same fair way as other nations.

In the email exchanges with the Academy did they give you any specific reasons for the decision?

Yes, of course. They said that the key creative participants were not Chinese. And I got confirmation today that Mark Johnson feels that the movie is French. That is not what the public in France felt. And that is not what the public in China felt; they saw the movie in Chinese with Chinese actors, with a Chinese story from a Chinese bestseller. Directed by a French guy, that is true, and with key people from France, but once again we could not have a co-production without having those points. We had to do some post production in France, but I spent a year doing post production in China and a few weeks in Paris to finalize the mix. It’s all legal; that’s the way co-productions function.

The Chinese have now submitted another film. Do you think there is anything the Chinese committee can do now?

China Film Group is very upset and they cannot understand why this movie that has been running in many festivals under the flag of China is suddenly kicked out. It’s a big blow for them because they basically came to us to raise the level of their production, that was the ambition — to start making movies that are not entirely local, that are international very much in the way that America has always done.

Do you think there will be repercussions for future foreign directors of Chinese films?

I do. More so, I know that it is going to be a problem with future co-productions. Because people who will want to invest in a partly-foreign crew — let’s say they want a good composer who they admire, or they want a director that has experience in the kind of movie they want to make — if this big investment cannot compete in the Oscar race, because now it is a “stateless” movie, the co-producing countries are going to be in trouble.

It’s discriminatory for films that are not in the English language but have ambition to be more international. The argument of the committee is that we want to help the local film industry, but are they really helping the local film industry by forbidding hiring competent technicians from around the world? Is that the way to help movies?

Rhonda Richford, The Hollywood Reporter, 14 жовтня 2015 року